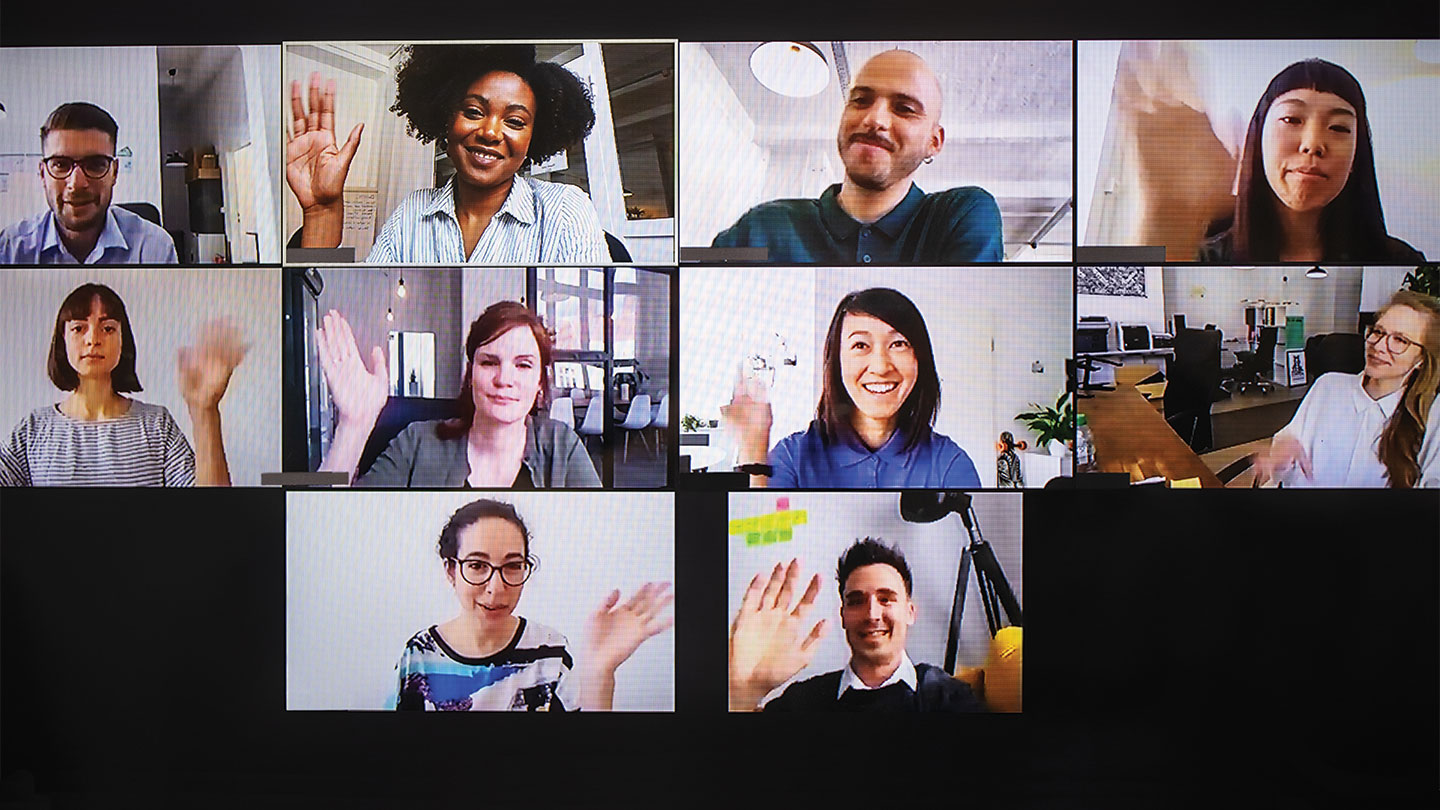

Eileen Donovan, an 89-year-old mom of seven residing in a Boston suburb, liked watching her daughter educate the class on Zoom throughout the coronavirus pandemic. She by no means imagined Zoom could be how her household ultimately attended her funeral.

Donovan died of Parkinson’s illness on June 30, 2020, abandoning her kids, 10 grandchildren, and 6 great-grandchildren. She all the time wished a raucous Irish wake. But solely 5 of her kids plus some native household could possibly be there in particular person, and no prolonged household or associates, on account of coronavirus issues. This was not the way in which that they had anticipated to mourn.

For online attendees, the ceremony didn’t finish with hugs or handshakes. It ended with a click on a pink “leave meeting” button, appropriately named for enterprise conferences, however not a lot else.

It’s the identical button that Eileen Donovan-Kranz, Donovan’s daughter, clicks when she finishes an English lecture for her class of undergraduate college students at Boston College. And it’s the identical method she and I ended our dialog on an unseasonably heat November day: Donovan-Kranz sitting in entrance of a window in her eating room in Ayer, Mass., and me in my bedroom in Manhattan.

“I’m not going to hold the phone during my mother’s burial,” she remembers considering. Just slightly over a year in the past, it might have appeared absurd to need to ask somebody to carry up a smartphone in order that others might “attend” such a private occasion. Donovan-Kranz requested her daughter’s fiancé to do it.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly modified the way in which folks work together with one another and with technology. Screens had been for reminiscing over cherished reminiscences, like watching VHS tapes or, more just lately, YouTube movies of weddings and birthdays which have already occurred. But now, we’re not simply watching reminiscences. We’re creating them on screens in actual time.

As social distancing measures pressured everybody to remain indoors and work together online, multibillion-dollar industries have needed to quickly alter to create experiences in a 2-D world. And though this idea of residing our lives online — from mundane work calls to memorable weddings or live shows — appears novel, scientists and science fiction writers have seen this actuality coming for many years.

In David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel Infinite Jest, videotelephony enjoys a short however frenzied reputation in a future America. Entire industries emerge to deal with folks’ self-consciousness on digital cameras. But ultimately, the trade collapses when folks notice they like the acquainted voice-only phone.

Despite a number of efforts by inventors and entrepreneurs to persuade us that videoconferencing had arrived, that actually didn’t play out. Time after time, folks rejected it for the common-or-garden phone or for different improvements like texting. But in 2020, dwell video conferences lastly discovered their second.

It took more than only a pandemic to get us right here, some researchers say. Technological advances over a long time along with the ubiquity of the technology acquired everybody on board. But it wasn’t straightforward.

Initial makes an attempt

On June 30, 1970 — precisely half a century earlier than Donovan’s loss of life — AT&T launched what it referred to as the nation’s first industrial videoconferencing service in Pittsburgh with a name from Peter Flaherty, the town’s mayor, to John Harper, chairman, and CEO of Alcoa Corporation, one of many world’s largest producers of aluminum. Alcoa had already been using the Alcoa Picturephone Remote Information System for retrieving info from a database using buttons on a phone. The information could be introduced on the videophone show. This was earlier than desktop computer systems had been ubiquitous.

This was not AT&T’s first videophone, nevertheless. In 1927, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover had demonstrated a prototype developed by the corporate. But by 1972, AT&T had a mere 32 models in service in Pittsburgh. The solely different metropolis providing industrial service, Chicago, hit its peak gross sales in 1973, with 453 models. AT&T discontinued the service within the late Nineteen Seventies, concluding that the videophone was “a concept looking for a market.”

About a decade after AT&T’s first try at commercialization, a band referred to as the Buggles launched the only “Video Killed the Radio Star,” the primary music video to air on MTV. The music reminded folks of the technological change that occurred within the Nineteen Fifties and ’60s when U.S. households transitioned away from radio as televisions grew to become more accessible to the lots.

The method tv achieved market dominance stored videophone builders bullish about their technology’s future. In 1993, optimistic AT&T researchers predicted: “the 1990s will be the video communication decade.” The video would change from one thing we passively consumed to one thing we interacted with in actual time. That was the hope.

When AT&T launched its VideoCellphone 2500 in 1992, prices started at a hefty $1,500 (about $2,800 in at the moment’s {dollars}) — later dropping to $1,000. The telephone had compressed coloration and a gradual body fee of 10 frames per second (Zoom calls at the moment are 30 frames per second), so pictures had been uneven.

Though the corporate tried to enchant potential clients with visions of the longer term, folks weren’t shopping for it. Fewer than 20,000 models offered within the 5 months after the launch. Rejection once more.

Building capability

Last June, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of AT&T’s first videophone launch, William Peduto, Pittsburgh’s mayor, and Michael G. Morris, Alcoa’s chairman on the time, spoke over videophone, simply as their predecessors had completed.

Several students, together with Andrew Meade McGee, a historian of technology and society at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, joined for a web-based panel to debate the rocky historical past of the videophone and its 2020 success. McGee informed me just a few months later that two issues are essential for a product’s precise adoption: “capacity and circumstance.” Capacity is all in regards to the technology that makes a product straightforward to make use of and reasonably priced. For videophones, it’s taken some time to get there.

When the Picturephone, which was launched by AT&T and Bell Telephone Laboratories, premiered at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City, a three-minute name price $16 to $27 (that’s about $135 to $230 in 2021). It was available only in booths in New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. (SN: 8/1/64, p. 73). Using the product required planning, effort, and cash — for low reward. The connection required a number of telephone strains and the image appeared on a black-and-white display screen in regards to the measurement of the moment’s iPhone screens.

These challenges made the Picturephone a tricky promotion. Marketing researchers Steve Schnaars and Cliff Wymbs of Baruch College on the City University of New York theorized why videophones hadn’t taken off a long time earlier than in Technological Forecasting and Social Change in 2004. Along with capability and circumstance, they argued, an important mass is essential.

For a technology to turn into common, the researchers wrote, all people want the cash and motivation to undertake it. And potential customers must know that others even have the machine — that’s the important mass. But when everybody makes use of this logic, nobody finally ends up shopping for the brand new product. Social networking platforms and courting apps face identical hurdles once they launch, which is why the apps create incentive packages to hook these all-important preliminary customers.

Internet entry

Even within the early 2000s, when Skype made a splash with its Voice over Internet Protocol, or VoIP, enabling internet-based calls that left landlines free, folks weren’t as linked to the web as they’re at the moment. In 2000, solely 3 % of U.S. adults had high-speed internet, and 34 % had a dial-up connection, in response to the Pew Research Center.

By 2019, the story had modified: Seventy-three % of all U.S. adults had high-speed internet at home; with 63 % protection in rural areas. Globally, the variety of web customers additionally elevated, from about 397 million in 2000, to about 2 billion in 2010 and three.9 billion in 2019.

But even after capability was established, we weren’t glued to our videophones as we’re at the moment, or as inventors predicted years in the past. Although Skype claimed to have 300 million customers in 2019, Skype was a service that folks sometimes used every so often, for worldwide calls or as one thing that took advance planning.

One long-time barrier that the Baruch College researchers cite from a casual survey is the aversion to all the time being “on.” Some folks would have paid further to not be on a digital camera of their residence, the identical method folks would pay further to have their telephone numbers neglected of phone books.

“Once people experienced [the 1970s] videophone, there was this realization that maybe you don’t always want to be on a physical call with someone else,” McGee says. Video calling builders had predicted these challenges early on. In 1969, Julius Molnar, vice chairman at Bell Telephone Labs, wrote that folks will probably be “much concerned with how they will appear on the screen of the called party.”

A scene from the Sixties cartoon The Jetsons illustrates this concern: George Jetson solutions a videophone name. When he tells his spouse Jane that her buddy Gloria is on the telephone, Jane responds, “Gloria! Oh dear, I can’t let her see me looking like this.” Jane grabs her “morning mask” — for the proper hair and face — earlier than making the decision.

That aversion to facing time is likely one of the components that stored folks away from video calling.

It took the pandemic, a change in circumstance, to power our hand. “What’s remarkable,” McGee says, “is the way in which large sectors of U.S. society have all of a suddenly been thrust into being able to use video calls on a daily basis.”

Circumstance shift

Starting in March 2020, necessary stay-at-home orders around the globe pressured us to hold on to an abridged type of our pre-pandemic lives, however from a distance. And one firm beat the competitors and rose to the highest inside a matter of months.

Soon after lockdown, Zoom grew to become a verb. It was the go-to alternative for every type of occasion. The excellent storm of capability and circumstance led to the important mass wanted to create the Zoom growth.

Before Zoom, a handful of corporations had been attempting to fill the house that AT&T’s videophone couldn’t. Skype grew to become the sixth most downloaded cellular app of the last decade from 2010 to 2019. FaceTime, WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook Messenger, and Google’s video chatting applications had been and nonetheless are among the many hottest platforms for video calls.

Then 2020 occurred.

Zoom beat its well-established rivals to rapidly turn into a family title globally. It gained important mass over different platforms by being straightforward to make use of.

“The fact that it’s been modeled around this virtual room that you come into and out of really simplifies the connection process,” says Carman Neustaedter of the School of Communication, Art and Technology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada, the place his staff has researched being current on video calls for work, residence and well being.

Zoom displays our actions in actual life — the place all of us stroll right into a room and everyone seems to be simply there. Casual customers don’t just have an account or join forward of time with these we wish to speak to.

Beyond design, there have been probably some market components at play as properly. Zoom linked early with universities, claiming by 2016 to be at 88 % of “the top U.S. universities.” And simply as Okay–12 colleges worldwide began closing final March, Zoom supplied free limitless assembly minutes.

In December 2019, Zoom statistics put its most variety of everyday assembly members (each paid and free) at about 10 million. In March 2020, that quantity had risen to 200 million, and the next month it was as much as 300 million. The method Zoom counts these customers is some extent of competition.

But these numbers nonetheless present some perception: If the product wasn’t straightforward and useful, we wouldn’t have stored using it. That’s to not say that Zoom is the proper platform, Neustaedter says. It has some apparent shortcomings.

“It’s almost too rigid,” he says.

It doesn’t permit for pure dialog; members need to take turns speaking, toggling the mute button to let others take a flip. Even with the flexibility to ship personal and direct messages to anybody within the room, the pure method we type teams and make small speak in actual life is misplaced with Zoom.

It’s additionally not perfect for events — it’s awkward to attend a party online when just one out of 30 associates can speak at a time. That’s why some folks have been enticed to change to different video calling platforms to host bigger online occasions, like graduations.

For instance, Remo, based in 2018, makes use of visible digital rooms. Everyone will get an avatar and might select a desk after seeing who else is there, to speak in smaller teams. Instead of Zoom breakout periods the place you’re assigned a room and might enter one other one by yourself, a platform like Remo lets you nearly see all of the rooms and choose one, exit it and go to a different one all without the assistance of a bunch.

The rigidity additionally ends in Zoom fatigue, that feeling of burnout related to overusing digital platforms to speak. Video calling doesn’t permit us to make use of direct eye contact or simply choose up nonverbal cues from physique language — issues we do throughout in-person conversations.

The psychological rewards of video calling — the prospect to be social — don’t all the time outweigh the prices.

Jeremy Bailenson, director of the Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford University, laid out four features that lead to Zoom fatigue within the Feb. 23 Technology, Mind, and Behavior. Along with cognitive load and decreased mobility, he blames the lengthy stretches of closeup eye gazing and the “all-day mirror.” When you consistently see yourself on a digital camera interacting with others, self-consciousness and exhaustion set in.

Bailenson has since modified his relationship with Zoom: He now hides the field that lets him view himself, and he shrinks the dimensions of the Zoom display screen to make gazing faces much less imposing. Bailenson expects minor adjustments to the platform will assist cut back the psychological heaviness we really feel.

Other challenges with Zoom have revolved around safety. In April 2020, the time period “Zoombombing” arose as teleconferencing calls on the platform had been hijacked by uninvited folks. Companies that might afford to change rapidly moved away from Zoom and paid for companies elsewhere. For everybody else who stayed on the platform, Zoom added near 100 new privateness, security, and security measures by July 2020. These adjustments included the addition of end-to-end encryption for all customers and assembly passcodes.

Anybody’s guess

In Metropolis, the 1927 sci-fi silent movie, a grasp of an industrial metropolis within the dystopian future makes use of 4 separate dials on a videophone to place a name by means of. Thankfully, inserting a video call is way simpler than it was predicted to be. But how a lot will we use this far-from-perfect technology as soon as the pandemic is over?

In the ebook Productivity and the Pandemic, released in January, behavioral economist Stuart Mills discusses why shoppers may hold using video calling. This pandemic could set up habits and preferences that won’t disappear as soon as the disaster is over, Mills, of the London School of Economics, and coauthors write. When persons are pressured to experiment with new behaviors, as we did with the videophone throughout this pandemic, the end result will be everlasting behavioral adjustments. Collaboration by means of video calling could stay common even after shutdowns carry now that we all know the way it works.

Events that require real-life interactions, similar to funerals and a few conferences, could not change a lot from what we had been used to pre-pandemic.

For different industries, video calling could change sure processes. For instance, Reverend Annie Lawrence of New York City predicts everlasting adjustments for elements of the marriage trade. People like the convenience of getting a wedding license online, and she or he’s been surprisingly in-demand doing video weddings because the pandemic began. Before, getting booked for officiating a marriage would require to discover months upfront. “Now, I’ve been getting calls on Friday to ask if I can officiate a wedding on Saturday,” she says.

Other sectors of society could notice that video calling isn’t for them, and can depart just some processes to be completed online. Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, for instance, said in a March 1 interview with Bloomberg Markets and Finance that he thinks a big portion of his workers will complete work within the workplace when that turns into potential once more. Culture is difficult to construct on Zoom, relationships are onerous to strengthen and spontaneous collaboration is troublesome, he stated. And there’s research that backs this.

But none of those adjustments or reversions to our earlier regular are a certain guess. We could discover, similar to in Wallace’s satirical storyline, that video calls are just too much stress, and the world will revert back to phone calls and face-to-face time. We could notice that even when the technology will get higher, the lifting of shutdowns and return to in-person life could imply fewer persons are out there for video calls.

It’s onerous to say which situation is almost definitely to play out in the long term. We’ve been terribly flawed about these items earlier.

More similar posts, you may like:

Neutron stars may not be as squishy as some scientists thought

![Demystifying Systems Thinking by Vasudhinity & Sahaj Foundation [May 15-Jul 4]: Register Now Demystifying Systems Thinking by Vasudhinity & Sahaj Foundation [May 15-Jul 4]: Register Now](https://www.noticebard.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/WhatsApp-Image-2021-04-18-at-12.43.40-PM.jpeg)