Picture a bridge fabricated from Lego blocks. One facet has three help items, the opposite two. How would you stabilize the bridge? Most folks would add a bit to the quick stack, a brand new examine suggests. But why not take away a bit from the taller stack? When it involves Lego blocks, elements in a recipe, or phrases in an essay, folks choose to add, not subtract.

People will be nudged to subtract as an alternative. But successfully altering that desire appears to require reminders or rewards. That’s the discovering of a new study. Its authors shared details of it within the April 8 Nature.

This desire for including isn’t restricted to constructing blocks, cooking, and writing. It may also contribute to modern-day excesses. Think about cluttered properties, extra authorities guidelines, and even a bent to pollute, says Benjamin Converse. He’s a behavioral scientist at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He worries that due to this bias towards including, “We’re missing an entire class of solutions.”

Converse was a part of a crew that first discovered this bias after they requested 1,585 examine contributors to deal with eight puzzles and issues. Each might be solved by including or eradicating issues. One puzzle required shading or erasing squares on a grid to make some sample symmetrical. In one other, folks may add or subtract objects on an inventory of supposed locations to enhance their trip expertise.

In every case, the overwhelming majority of individuals were selected to add not subtract. For the occasion, of 94 contributors who accomplished the grid process, 73 added squares. Another 18 eliminated squares. Three merely reworked the unique variety of squares.

The researchers suspect that most individuals default to including just because subtracting by no means even involves thoughts. But using a collection of managed trials, the crew was capable of nudge recruits towards the minus possibility.

Hint, trace . . .

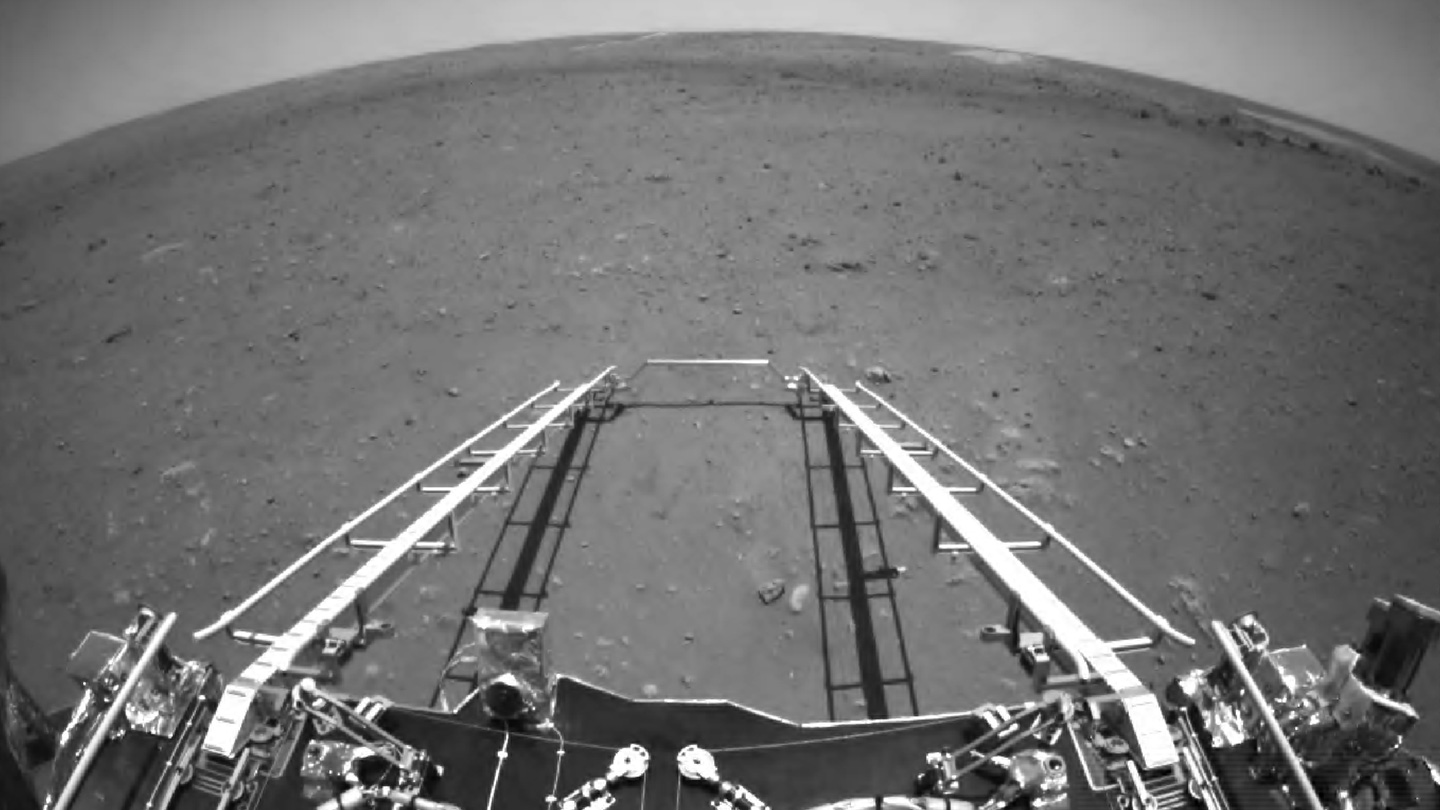

In one take a look at, the crew provided 197 folks wandering around a crowded college website a greenback to unravel a puzzle. People considered a Lego construction. It had a determine standing atop a platform with a big pillar behind her. A single block on one nook of the pillar supported a flat roof. Researchers requested the contributors to stabilize the roof to keep away from squashing the determine.

The researchers warned 98 contributors that “each piece you add costs 10 cents.” Yet solely 40 of them thought to take away the destabilizing block so that the roof may relax on prime of the vast pillar under. The different 99 contributors had been informed concerning the 10-cent price of every additional block. But these folks additionally discovered “removing pieces is free.” That cue prompted 60 of them to take away the block.

The practice did assist contributors to bring to mind that elusive possibility of eradicating (subtracting) one thing. In a variation on the grid take a look at, the place subtraction yielded the perfect answer, contributors received three follow runs. When they carried out the precise process, more folks now selected to subtract squares than did those that labored this downside without following.

Throwing unrelated info at folks lowered the possibility they’d subtract one thing. In reality, folks added even more when combating info overload, the brand new examine studies.

“When people try to make something better … they don’t think that they can remove or subtract unless they are somehow prompted to do so,” says Gabrielle Adams. She’s a behavioral scientist who additionally works at the University of Virginia.

On some deep stage, folks appear to comprehend that subtraction comes much less naturally than addition, the authors say. That could also be what’s behind such sayings as “less is more” and Marie Kondo’s now-notorious suggestion that individuals rid themselves of all the things that fail to spark pleasure.

But curbing our love of extra will take more than nudges and transparent thoughts suspects Hal Arkes. He’s a researcher at Ohio State University in Columbus. There, he researches judgment and decision-making. Organizational and political leaders actually hate reducing the fats, he notes. They appear to really feel that “if you add more people and more dollars, you won’t make any enemies,” Arkes says. “You’ll just make friends.” For them, he argues, “subtraction has serious downsides.”

Source

Check below for more interesting stories:

This praying mantis inflates a strange pheromone gland to lure mates(Opens in a new browser tab)